Bermuda Petrel Pterodroma cahow

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Catalan | petrell de les Bermudes |

| Czech | buřňák bermudský |

| Danish | Bermudapetrel |

| Dutch | Bermudastormvogel |

| English | Bermuda Petrel |

| English (United States) | Bermuda Petrel |

| French | Pétrel des Bermudes |

| French (France) | Pétrel des Bermudes |

| German | Bermudasturmvogel |

| Hungarian | Bermudai viharmadár |

| Icelandic | Brimdrúði |

| Japanese | バミューダミズナギドリ |

| Norwegian | bermudapetrell |

| Polish | petrel bermudzki |

| Russian | Бермудский тайфунник |

| Serbian | Bermudska burnica |

| Slovak | tajfúnnik bermudský |

| Slovenian | Bermudski švigavec |

| Spanish | Petrel Cahow |

| Spanish (Spain) | Petrel cahow |

| Swedish | bermudapetrell |

| Turkish | Bermuda Fırtınakuşu |

| Ukrainian | Тайфунник бермудський |

Introduction

Perhaps the world’s most storied seabird, Bermuda Petrel (Pterodroma cahow)—or Cahow, as it is called on Bermuda—was little more than legend until its rediscovery and description in the twentieth century, more than 300 years after it had vanished from human experience.

When Cristóbal Colón sailed past Bermuda in 1492, an estimated half million pairs of Bermuda Petrel nested throughout the Bermuda archipelago. But within a few decades, owing to human exploitation and to the introduction of hogs by Spanish seafarers, the birds had become scarce, their nesting limited to remote cliffs and offshore islets. With the advent of permanent English colonists in the early 1600s, rats, cats, hogs, and dogs had eliminated most petrels nesting on the main islands, and continued human exploitation of the petrels for food also took a heavy toll on the species. In 1614, rats (apparently from a captured Spanish ship transporting grain) devoured so much of the settlers' crops and provisions that Bermuda's governor, Richard Moore, evacuated the colonists to Cooper's Island, which still had abundant bird resources (and sea turtles), so that they might avoid starvation. Many of the breeding petrels there were consumed. During the next breeding season, the birds were so rarely encountered that the islands' new governor, Daniel Tucker, urged public restraint in eating the petrels—the famed "Proclamation gainst the spoyle and havocke of the cahowes". But by 1620, the bird was no longer seen and was presumed extinct.

Glimmers of the persistence of Bermuda Petrels into modern times began on 22 February 1906, when Louis L. Mowbray, Director of the Bermuda Aquarium, found a live gadfly petrel in a crevice on Gurnet Rock, a stack lying off Castle Island. The bird was subsequently identified by ornithologist Thomas Bradlee as what we now call Mottled Petrel (Pterodroma inexpectata) and was published as such later in the year. A decade later, R. W. Shufeldt compared the bones of Mowbray's bird to abundant fossil bones of gadfly petrels collected by Mowbray at Bermuda's Crystal Cave—and determined that they were of the same species. And so Mowbray, with John T. Nichols, described "Æstrelata cahow" to science in 1916, indicating that this specimen was indeed of the long-lost gadfly petrel called Cahow that once was so abundant in this location.

Hoping to rediscover the species in life, William Beebe of the New York Zoological Society searched Bermuda in spring 1935, without success. However, on 8 June 1935, Beebe was given a specimen of an unfamiliar seabird that had struck the St. David's lighthouse and sent it to Robert Cushman Murphy of the American Museum of Natural History in New York—who identified it as a newly fledged Bermuda Petrel. Six years later, in 1941, Mowbray received a live Bermuda Petrel, found by a member of the Bermuda Volunteer Rifle Corps, that had collided with a radio antenna tower (or wires) in St. George's. The bird was rehabilitated and released two days later. And in 1945, at the close of the Second World War, U.S. Army officer Fred T. Hall found the remains of several gadfly petrels at St. David's, including the corpse of an adult on 14 March, and notified biologists at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Again, these proved to be the bird described by Mowbray and Nichols, and later Beebe, as Bermuda Petrel.

At last, in January 1951, a scientific expedition was organized to search for the bird, led by Louis S. Mowbray (son of the 1906 discoverer) and by Robert Cushman Murphy and his wife, Grace E. B. Murphy. During a careful survey of the islets around Castle Harbor, they found seven nesting pairs of Bermuda Petrel, and the news of the discovery quickly spread around the world through the news media with rare fanfare, at least for a seabird.

Accompanying Mowbray and the Murphys on the expedition was a local Bermudian schoolboy, David B. Wingate, who was present when the first petrel was found, on 28 January 1951. Just two years later, the young Wingate acquired a specimen of Bermuda Petrel from an antique dealer; it proved to be from the 1800s, from the collection of John Tavernier Bartram, a naturalist who searched for the species without realizing he had a specimen in his possession. After graduating from Cornell University in 1957, Wingate returned to Bermuda to work on petrel conservation, under the auspices of the Bermuda Aquarium. He would become Bermuda's Conservation Officer and the birds’ outspoken champion over the next five decades.

During that time, the tiny population of petrels was nearly lost again, first to a terrible nest-site competition with White-tailed Tropicbirds (Phaethon lepturus), first noted in 1951, then to egg-shell thinning caused by DDT. Wingate reduced, then eliminated the tropicbird problem by constructing tropicbird-excluding baffles on active petrel burrows, by digging and constructing artificial burrows, which the petrels accepted, and later by a successful campaign to supply tropicbirds with artificial nest "igloos," placed away from petrel nesting areas.

In recent decades, overwashing of nest burrows during frequent episodes of hurricane surge has resulted in petrel mortality and in the destruction of nest burrows, prompting Wingate and Bermuda's new Senior Terrestrial Conservation Officer, Jeremy Madeiros, to commence a program in 2002 of translocating young petrels to artificial burrows on higher ground, on Nonsuch Island, which Wingate has reforested to its precolonial state over the past 50 years. As of spring 2013, with a total of 105 nesting pairs of Bermuda Petrel (12 of these on Nonsuch), there is guarded optimism for the survival of this striking seabird.

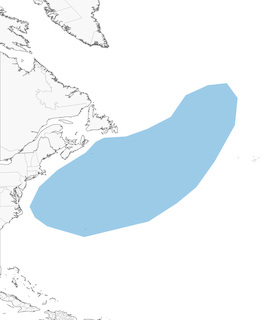

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding