Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Catalan | bosquerola aladaurada |

| Czech | lesňáček zlatokřídlý |

| Danish | Gulvinget Sanger |

| Dutch | Geelvleugelzanger |

| English | Golden-winged Warbler |

| English (United States) | Golden-winged Warbler |

| French | Paruline à ailes dorées |

| French (France) | Paruline à ailes dorées |

| German | Goldflügel-Waldsänger |

| Greek | Χρυσόφτερη Πάρουλα |

| Haitian Creole (Haiti) | Ti Tchit zèl dore |

| Hebrew | סבכון זהוב-כנף |

| Hungarian | Aranyszárnyú hernyófaló |

| Icelandic | Gullskríkja |

| Japanese | キンバネアメリカムシクイ |

| Lithuanian | Geltonsparnis kirmlesys |

| Norwegian | gullvingeparula |

| Polish | lasówka złotoskrzydła |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Mariquita-d'asa-amarela |

| Romanian | Omidar cu aripă aurie |

| Russian | Желтокрылая червеедка |

| Serbian | Zlatokrila cvrkutarka |

| Slovak | horárik zlatokrídly |

| Slovenian | Zlatoperuti peničar |

| Spanish | Reinita Alidorada |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Reinita Alidorada |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Bijirita alidorada |

| Spanish (Dominican Republic) | Cigüita Ala de Oro |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Reinita Alidorada |

| Spanish (Honduras) | Chipe Ala Dorada |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Chipe Alas Amarillas |

| Spanish (Panama) | Reinita Alidorada |

| Spanish (Peru) | Reinita de Ala Dorada |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Reinita Alidorada |

| Spanish (Spain) | Reinita alidorada |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Reinita Alidorada |

| Swedish | guldvingad skogssångare |

| Turkish | Altın Kanatlı Ötleğen |

| Ukrainian | Червоїд золотокрилий |

Vermivora chrysoptera (Linnaeus, 1766)

Definitions

- VERMIVORA

- vermivora / vermivorum / vermivorus

- chrysoptera / chrysopterum

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Golden-winged Warbler Vermivora chrysoptera Scientific name definitions

Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020

Text last updated March 25, 2011

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Vocalizations

Extensively studied, especially comparison with vocalizations of Blue-winged Warblers and their hybrids (Gill and Lanyon 1964, Ficken and Ficken 1966, Ficken and Ficken 1968c, Ficken and Ficken 1969, Ficken and Ficken 1970, Gill and Murray 1972b). Murray and Gill (Murray and Gill 1976) provide a synopsis of responses to song playback by both species. Highsmith (1989Highsmith 1989b, Highsmith 1989a) summarized studies of Golden-winged Warbler song types and analyzed their phenology, behavioral context, geographic variation, and features used in species discrimination.

Development

Not studied in Golden-winged Warblers, but influence of learning on song development in Blue-winged Warblers (Kroodsma 1988) probably pertains. Naive, hand-reared Blue-winged Warblers exposed to manipulated songs of wild males sang poor renditions of the stereotyped song of wild adults, suggesting that song structure is partially learned and partially innate.

Vocal Array

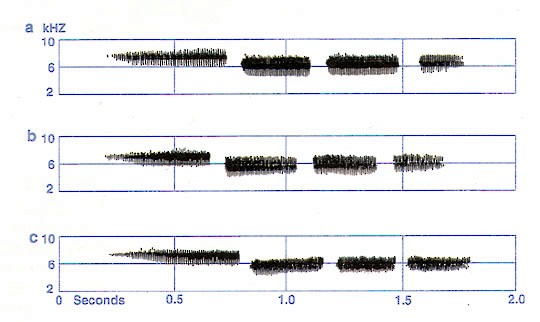

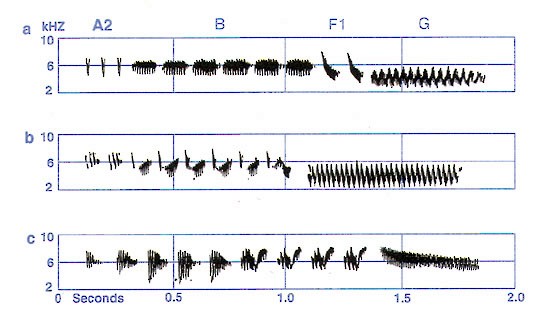

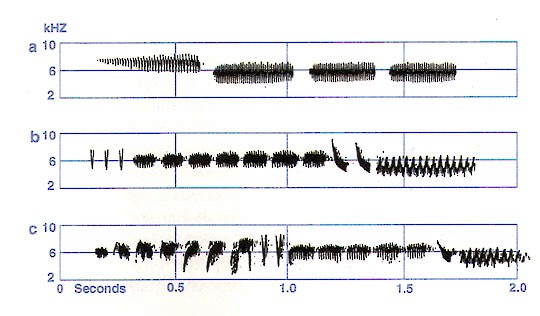

Two song types ("type I" and "type II") recognized (Ficken and Ficken 1966, Kroodsma 1988, Highsmith 1989b); each sibilant and unmusical. Sonograms (Figures 2-4) may be compared to additional sonograms of both song types in Gill and Lanyon (Gill and Lanyon 1964), Gill and Murray (Gill and Murray 1972b) and Highsmith (1989Highsmith 1989b, Highsmith 1989a).

Type I song described as zeee bee bee bee. Zeee note slightly higher in pitch; number of bee notes 1 to 6. Type I singing characterized by a low mean song rate (3.9 songs/min, n = 5 males), lack of chip notes between songs, and absence of flight song displays (Highsmith 1989b). Little variation in type I song delivery rates among males even during counter-singing.

Singing is infrequent for the first few days after arrival on the breeding territory; birds respond poorly to playbacks (Murray and Gill 1976). Type I song predominates, especially at dawn. A few days later, frequent song bouts begin, i.e., a sequence of songs that typically last a few minutes or, among unmated males, hours. Bouts of type I song diminish after pair formation and continue to decline during the rest of the breeding season; by mid-season, heard rarely except shortly after sunrise. The number of bee notes in type I song also declines after pair formation; the long form of type I song apparently serves primarily to attract mates. Type I song may increase abruptly if a mate is lost and continues at high frequency throughout much of a breeding season for unmated males. Males sometimes sing frequently off territory when females begin incubation. The number of bee notes declines also in response to playbacks of type I song. Responding males often whisper a type I song, sometimes abbreviated to a single zeee note.

Type I song is usually given from a high perch. For most males, this perch is located near the nest; for others, whose territory is far from another male, the usual song perch is sited near the territorial boundary of the nearest neighbor and may be 200-300 m from the nest (JLC). Males may use the same perch on consecutive years (JLC).

Type II song (Figure 3) sounds like a sibilant, rapid stutter followed by a lower buzzy note. Use of type II song increases 2 to 4 d after arrival on the breeding territory. By that time males sing type II song interspersed with a few chips almost non-stop for about 30 min before sunrise. These singing bouts are given daily until the young depart the nest. Bouts of type II song usually occur at the edge of a territory closest to a neighbor (Highsmith 1989Highsmith 1989b, Highsmith 1989a). Type II song is repeated at a frequency of 6 to 10/min, about twice the frequency of type I songs given later in the day (Highsmith 1989b).

Pre-dawn singing bouts may be interrupted by flight song (Figure 4). Highsmith (Highsmith 1989a) notes "Flight song displays can be given at any point in the type II bout, but 5 of the 11 males in which I observed it used it frequently as one of their very first songs of the morning. Displaying males flew up in an arching path, flapped or glided down to the same or a different perch (similar to description for other parulines in Ficken and Ficken 1962)." Males sometimes give brief bouts of type II song while accompanying females during courtship and nest building (JLC).

The use of type II song increases during intrasexual encounters and following playbacks of either song type. The frequency of type I song decreases in both circumstances. The principal functions of type I and type II song appear to be mate attraction and territorial defense, respectively (Ficken and Ficken 1966, Murray and Gill 1976). Highsmith (Highsmith 1989b) suggested that males use different renditions of their two song types in a graded series. When undisturbed or in the presence of a female, males generally sing long type I songs (zeee bee bee bee) but shorten these when interacting with another male (zeee bee). If the dispute intensifies, males switch to type II songs. Thus, long type I songs and type II songs appear to lie at opposing ends of a motivation continuum.

Calls

Males and females utter tzip call during courtship (Ficken and Ficken 1968a), but rarely after nest building. Zeee-like call notes frequently given as young leave nest. Adults land above the nest and chip, as if "urging" young to leave. Males from adjacent territories often come to a nest as young depart. This may lead to pursuit by the resident male, who gives type II songs. For several days following nest departure both young and adults communicate with this zeee call. Adults give this call upon return to the area where mobile fledglings were last fed and the young may reciprocate with a virtually identical note. At the nest an alarmed female may give a prolonged, ascending scold.

Interspecies Discrimination

Both Golden-winged and Blue-winged warblers use type I and type II song in similar behavioral contexts. Type I songs for both species have similar tonal quality and rhythm, yet are easy to distinguish. Individual males may have distinct songs. Both species may respond to each other's type I song; discrimination is better in regions of sympatry (Murray and Gill 1976). Playback experiments in allopatric populations of Golden-winged Warblers in Minnesota and Blue-winged Warblers in Massachusetts showed that males based their discrimination of type I songs on species-typical differences in frequency (Hz), amplitude modulation, and overall song pattern (Highsmith 1989a).

Type II songs of both species can be quite similar, especially where their range overlaps. Because of pronounced geographical variation in type II songs (Figure 3), a Golden-winged Warbler song might more closely resemble a neighboring Blue-winged Warbler than it would another Golden-winged Warbler from a distant population (T. Highsmith pers. comm.). In a sympatric population in Michigan only three of 12 Golden-winged Warbler males failed to respond of Blue-winged Warbler type II song while seven responded strongly (Gill and Murray 1972b). Highsmith (Highsmith 1989a) found that Golden-winged Warblers in Minnesota responded more strongly to local type II songs than to songs from distant populations of either Golden-winged or Blue-winged warblers.

Hybrid And Cross-Species Singing

Songs of hybrids match those of the parental species and are not intermediate in form (Ficken and Ficken 1966, Gill and Murray 1972b). In north-central New York, 19 of 21 Brewster's Warblers sang a Golden-winged type I song (Confer et al. 1991). Yet all of three hybrids recorded in central Michigan (Gill and Murray 1972b) and one of two hybrids described in a study of central New York study (Ficken and Ficken 1966) sang Blue-winged type I song. Occasionally a Golden-winged Warbler with non-introgressed plumage will sing a Blue-winged Warbler type I song, e.g., one of 14 in central Michigan (Gill and Murray 1972b) and one of six in central New York (Ficken and Ficken 1966). Two Lawrence's Warblers alternately sang the type I song of Golden-winged and Blue-winged warblers (Gill and Murray 1972b). Such alternate or bivalent singing has been reported for two (non-introgressed) Golden-wing (Russell 1976a, JLC) and one (non-introgressed) Blue-wing (Short 1963).

Census techniques that use bird calls face severe difficulty with Golden-winged and Blue-winged warblers. Hybrids will be identified as one or the other species. The pre-dawn singing bouts of type II song are very similar for both species, and difficult to distinguish.

Nonvocal Sounds

Not known.

(a) northern Minnesota. (b) central Michgan. (c) southern Ontario. All sonograms were prepared on a Kay Elemetrics Model 7029A Sonograph (600 Hz filter).

(a) northern Minnesota. (b) central Michigan. (c) southern Ontario.

(a) Type I song. (b) Type II song. (c). modified type II song used in flight song display. From Highsmith (1989a).