Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Catalan | picot negre bec d'ivori |

| Czech | datel knížecí |

| Dutch | Grote Ivoorsnavelspecht |

| English | Ivory-billed Woodpecker |

| English (United States) | Ivory-billed Woodpecker |

| French | Pic à bec ivoire |

| French (France) | Pic à bec ivoire |

| German | Elfenbeinspecht |

| Japanese | ハシジロキツツキ |

| Norwegian | elfenbeinsspett |

| Polish | dzięcioł wielkodzioby |

| Russian | Белоклювый дятел |

| Serbian | Belokljuna ćubasta žuna |

| Slovak | chochlák slonovinovozobý |

| Spanish | Picamaderos Picomarfil |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Carpintero real |

| Spanish (Spain) | Picamaderos picomarfil |

| Swedish | elfenbensnäbb |

| Turkish | Fildişi Gagalı Ağaçkakan |

| Ukrainian | Дятел-кардинал великодзьобий |

Campephilus principalis (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- CAMPEPHILUS

- principalis

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Ivory-billed Woodpecker Campephilus principalis Scientific name definitions

Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020

Text last updated January 1, 2002

Diet and Foraging

Feeding

Main Foods Taken

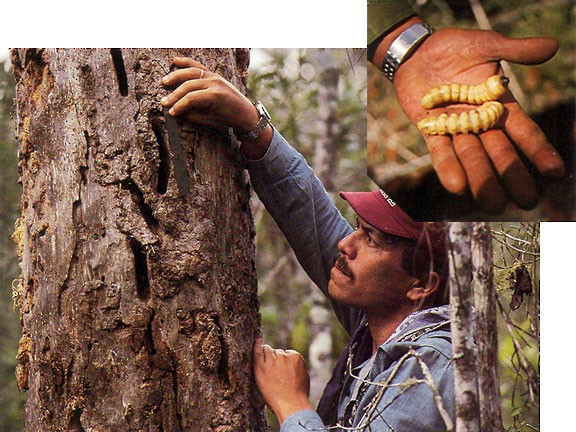

In both the U.S. and Cuba, beetle larvae of the families Cerambycidae, Buprestidae, and Elateridae (Allen 1939b; Tanner Tanner 1941, Tanner 1942bb).

Microhabitat For Foraging

Herb Stoddard (fide Dennis 1967b) referred to Ivory-billed Woodpecker as a “disaster species,” moving into areas where trees had been killed and feeding on beetle larvae found beneath the bark of recently dead trees. In Mississippi Delta and other areas, flooding, as well as storms, often caused the extensive tree mortality needed to support abundant beetle populations (Tanner Tanner 1941, Tanner 1942bb). In Florida and other coastal regions adjacent to pinelands, fires were often the source of tree mortality and an integral part of the ecosystem supporting Ivory-billeds (Jackson 1988c). In some areas, especially pinelands adjacent to swamps, Ivory-billeds made extensive use of recently burned areas for foraging (e.g., Ridgway 1898b, Tanner 1942bb, Stoddard 1969).

Allen (Allen 1939b: 2) thought that there might be geographic or habitat differences in the foraging ecology of Ivory-billeds, noting that although the birds nested in a baldcypress swamp, they did most of their feeding along its borders on recently killed young pines that were infested with beetle larvae. This may simply reflect the species' flexibility in foraging, however. Allen (Allen 1939b) noted individuals even foraged on the ground like flickers (Colaptes sp.) to feed among palmetto roots on a recent burn. Where early settlers girdled trees to clear land, Ivory-billeds were often quick to find and feed on such dying trees (Audubon 1842).

In the Singer Tract in Louisiana, Tanner (Tanner 1942bb) found Ivory-billeds foraged primarily on sweetgum (43% of 101 observations) and Nuttall's oak (27% of observations). These species made up 31% of the trees in the forest >30 cm dbh, but 69% of foraging observations. Sugarberry (12% of observations; 15% of forest trees >30 cm dbh) was the only other tree species used extensively by foraging Ivory-billeds. Overall, about 87% of foraging in Louisiana was on trees >30 cm diameter (Tanner 1941).

In Cuba, Lamb (Lamb 1957) found Ivory-billed Woodpeckers divided their foraging efforts about equally between pines and hardwoods.

Food Capture And Consumption

In both the U.S. and Cuba, primary foraging method was to strip bark from recently dead trees by using its bill much like a carpenter's wood chisel to reveal beetle larvae (Figure 2); also sought wood-boring insects in small trees and fallen logs, splintering them in its search for food (Allen 1939b). Less often would excavate in a manner similar to Pileated Woodpeckers—digging deeper, slightly conical holes into rotted wood in search of larvae (Tanner 1942bb, Lamb 1957). In a letter to Jim Tanner (4 Sep 1939), Herb Stoddard, who knew Ivory-billeds in his youth, described what he believed was Ivory-billed work on pines that had been killed by a hurricane in n. Florida: “The larger portion of the bark of these pines had been removed while it was still quite tightly attached, the evidence being left on the tree being comparable to that a man might leave who knocked off the bark with a cross hatching motion with a heavy screwdriver.”

This description fits the work Tanner described on hardwood trees in the Singer Tract and that I saw on pines in the mountains of e. Cuba in 1987 and 1988. Dennis (Dennis 1984) contrasted the structure of Ivory-billed and Pileated bills and their foraging methods, suggesting that the former was specialized to take advantage of larger larvae in recently dead large trees that were inaccessible to the less chisel-like bill of the Pileated, but that the Pileated was more of a generalist and as a result did well in a diversity of habitats while the Ivory-billed disappeared as the virgin forests (larger trees) disappeared.

Diet

In the Carolinas, Wilson (Wilson 1811) found numerous 2- to 3-in (5-8 cm) beetle larvae that he described as a dirty cream color with a black head. This is consistent with many species of cerambycid beetle larvae. Gosse (Gosse 1859) also reported a large “ Cerambyx ” as well as the seeds of cherry (Prunus sp.) in the stomach of one Alabama bird; a second had only cherries in its stomach.

F. E. L. Beal (Beal 1911) examined the contents of 2 stomachs from Ivory-billed Woodpeckers, although he did not give a locality for the specimens. One contained 32 and the other 20 cerambycid beetle larvae, and these constituted 38% of the food in the stomachs. Also included were engraver beetles (Scolytidae), including at least 3 species (Ips avulsus, I. calligraphus, and I. grandicollis) in 1 stomach. All 3 of these engraver beetles are species that feed on pines (Baker 1972). Total animal food made up 39% of the contents and vegetable matter the other 62%. One stomach contained the fruit of the southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora), also known today as bull bay and reported by Beal as Magnolia foetida . The other stomach included pecan (Carya sp.) nuts.

Cottam and Knappen (Coues 1874a) examined the contents of 3 Ivory-billed Woodpecker stomachs, apparently the first 2 of which were the ones examined by Beal. They reported that the first 2 stomachs came from birds collected by Vernon Bailey on 26 Nov 1904 at Tarkington, TX. The third stomach came from a bird collected at Bowling Green, W. Carroll Parish, LA, on 19 Aug 1903, by E. L. Mosely. The first 2 stomachs were filled (see Oberholser 1974: 527–530); they received only the stomach contents of the third bird. The combined sample included 46% animal food and 54% plant material. Most of the animal material (45% of the total sample, USFWS files fide Tanner 1942bb) was composed of cerambycid beetles. Two species of cerambycids were identified as Parandra polita and Stenodontus dasystomus . P. polita is a long-horned beetle that has been described as “rather rare” in the s. U.S., but common in Mexico and Central America (Doane et al. 1936), thus potentially providing a specific dietary link between Ivory-billed and Imperial woodpeckers. These beetles feed on the heartwood of old and weakened hardwoods. Stenodontus dasystomus, known as the “hardwood-stump borer,” is found only in the e. U.S., and its larvae also consume the heartwood of living trees (Headstrom 1977). Tanner (Tanner 1942bb) iden-tified the larvae of Stenodontus dasystomus as prey brought in the bill of adults to nestlings in the Singer Tract.

Cottam and Knappen (Coues 1874a) broke down the plant component of the diet as including 14% southern magnolia seeds, 27% hickory and pecan (Carya illinoiensis) nuts, and 13% poison ivy seeds (Rhus radicans). They also noted a trace of gravel and fragments of an unidentified gall in the third stomach. E. A. McIlhenny (in Bendire 1895) suggests Ivory-billeds ate acorns.

Although the favored food of Ivory-billeds appears to have been the large larvae of some long-horned beetles (Cerambycidae; probably because of their size and hence volume of nutrients per larva), they have also been reported attracted to trees killed during what sounds like southern pine beetle (Dendroctonus frontalis; Scolytidae) outbreaks. Reports of Ivory-billeds foraging on downed wood suggests the probability that they also readily took the large larvae of other beetles, such as the horned passalus (Popilius disjunctus; Passalidae).

Audubon (Audubon 1842) and others described considerable use of fruit and berries in season, noting that grapes (Vitis sp.), persimmons (Diospyros virginiana), and hackberries were eaten, ripe grapes with “great avidity.”

In Cuba, diet probably similar to that in the U.S. Lamb (Lamb 1957: 10) observed an Ivory-billed Wood-pecker foraging at a branch that he later found to be full of larvae and adults of a small beetle (Melasidae; Hypocoelus). Lamb also collected large larvae of Buprestidae from pines, and I collected very large larvae of Cerambycidae from dead pines that showed sign of Ivory-billed scaling (Figure 3). Gundlach (fide F. García pers. comm.) noted Ivory-billeds feeding on arboreal termites (Isoptera). García (García 1987) mentions them eating seeds.

Food Selection and Storage

No information.

Nutrition and Energetics

No information.

Metabolism and Temperature Regulation

No information.

Drinking, Pellet-Casting, and Defecation

No information.

Ivory-billed Woodpeckers use their strong bills to strip bark from recently dead trees in search of beetle larvae, a major source of food for the species. Drawing by Julie Zickefoose.

736