Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Knoet |

| Albanian | Gjelëza e madhe |

| Arabic | دريجة حمراء |

| Asturian | Mazaricu gordu |

| Azerbaijani | İslandiya qumluq cüllütü |

| Basque | Txirri lodia |

| Bulgarian | Голям брегобегач |

| Catalan | territ gros |

| Chinese | 紅腹濱鷸 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 红腹滨鹬 |

| Croatian | hrđasti žalar |

| Czech | jespák rezavý |

| Danish | Islandsk Ryle |

| Dutch | Kanoet |

| English | Red Knot |

| English (United States) | Red Knot |

| Faroese | Íslandsgrælingur |

| Finnish | isosirri |

| French | Bécasseau maubèche |

| French (France) | Bécasseau maubèche |

| Galician | Pilro groso |

| German | Knutt |

| Greek | Κοκκινοσκαλίδρα |

| Haitian Creole (Haiti) | Mòbèch |

| Hebrew | חופית להקנית |

| Hungarian | Sarki partfutó |

| Icelandic | Rauðbrystingur |

| Indonesian | Kedidi merah |

| Italian | Piovanello maggiore |

| Japanese | コオバシギ |

| Korean | 붉은가슴도요 |

| Latvian | Lielais šņibītis |

| Lithuanian | Islandinis bėgikas |

| Malayalam | ചെമ്പൻ നട്ട് |

| Mongolian | Шармаг элсэг |

| Norwegian | polarsnipe |

| Persian | تلیله خاکستری |

| Polish | biegus rdzawy |

| Portuguese (Angola) | Seixoeira |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | maçarico-de-papo-vermelho |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Seixoeira |

| Romanian | Fugaci mare |

| Russian | Исландский песочник |

| Serbian | Velika sprutka |

| Slovak | pobrežník hrdzavý |

| Slovenian | Veliki prodnik |

| Spanish | Correlimos Gordo |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Playero Rojizo |

| Spanish (Chile) | Playero ártico |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Correlimos Grande |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Zarapico raro |

| Spanish (Dominican Republic) | Playero Pechirrojo |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Playero Rojo |

| Spanish (Honduras) | Playero Rojo |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Playero Rojo |

| Spanish (Panama) | Playero Rojo |

| Spanish (Paraguay) | Playerito rojizo |

| Spanish (Peru) | Playero de Pecho Rufo |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Playero Gordo |

| Spanish (Spain) | Correlimos gordo |

| Spanish (Uruguay) | Playero Rojizo |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Playero Pecho Rufo |

| Swedish | kustsnäppa |

| Thai | นกน็อตเล็ก |

| Turkish | Büyük Kumkuşu |

| Ukrainian | Побережник ісландський |

Calidris canutus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- CALIDRIS

- calidris

- canutus

- Canutus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Red Knot Calidris canutus Scientific name definitions

Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020

Plumages, Molts, and Structure

Plumages

Red Knots have 10 functional primaries, 14-15 secondaries (including 3 tertials), and 12 rectrices; Calidrine sandpipers are diastataxic (see Bostwick and Brady 2002) indicating that a secondary has been lost evolutionarily between what we now term s4 and s5. Appearance of breeding birds shows average geographic differences but these may result more from interactions of location-specific effects of molt strategies on plumage than on genetic differences (Pyle 2008).

The following molt and plumage descriptions pertain primarily to populations breeding in the central Canadian Arctic (C. c. rufa) with average geographic variation noted as appropriate; see Systematics: Geographic Variation for information on the 5 other recognized subspecies breeding throughout Holarctic regions. Geographic variation in molt strategies is correlated with latitude of wintering grounds (Pyle 2008, Summers et al. 2010; see below); slight sex-specific variation in Prealternate molt strategies has also been reported (see below) but confirmation needed.

Following based primarily on detailed plumage descriptions in Witherby (Witherby 1924), Palmer (1967b), Oberholser (1974), Cramp and Simmons (Cramp and Simmons 1983), Hayman et al. (1986), Higgins and Davies (1996), Paulson (2005), and O'Brien et al. (2006); see Prater et al. (Prater et al. 1977) and Pyle (2008) for specific age-related criteria. Sexes show similar appearances in most plumages but show average differences in Definitive Alternate Plumage (see below). Definitive Plumages typically assumed at Second Basic and Second Alternate Plumages.

Natal Down

Present Jun-Jul, on or near natal territory. Description based on Fjeldså 1977, except as noted. Newly hatched chicks completely downy; upper parts dull, blackish brown with very little buff (especially in North America), abundantly speckled with rows of white (sometimes cinnamon) dots forming rudimentary hourglass pattern, but with more prominent white bands of loose, large “powder puffs” to each side; wing pads often with diffuse “powder puffs” of white at tip. Dark median crown runs from bill to eye; partial stripes run below eye; superciliary zone densely mottled with black; prominent mottled markings and lines in auriculars and as a line across occiput. Chin white, with white patch on either side (Palmer 1967b). Coloring becomes lighter gray on sides, and then light on under parts, with buffy-grayish wash on breast.

Juvenile (First Basic) Plumage

Present primarily Jun–Oct, on breeding grounds and during part or all of southbound migration. Similar to Definitive Basic Plumage in overall appearance but dorsal contour feathering (upperwing coverts, scapulars, tertials) with white outer margin, bordered internally by parallel dark band; usually worn off during Oct-Dec in Southern Hemisphere wintering populations. Breast sometimes washed with pinkish buff when fresh and upper breast marked with brown or dark streaks and dots.

Formative Plumage

"First Basic" or "Basic I" plumage of Humphrey and Parkes (1959) and later authors; see revision by Howell et al. (2003). Present variably Oct–Mar, primarily on winter grounds. Similar to Definitive Basic plumage, but scapulars, lower back, tertials, and upperwing coverts are mixed Juvenile and Formative during Oct-Dec. Retained Juvenile feathers can show paler fringing of Juvenile plumage when fresher, and usually (especially outer upperwing greater coverts) contrastingly worn in winter and spring. Remiges and rectrices remain largely unmolted in birds wintering in the Northern Hemisphere; average narrower and more worn than Basic feathers of older birds. In many birds wintering in the Southern Hemisphere, outer primaries and inner secondaries are replaced Jan-May in an eccentric pattern (Pyle 2008). Molt limits occur between a block of Juvenile outer secondaries and inner primaries in the center of the wing (varying from 6 to 18 feathers) and fresher, replaced formative inner secondaries and outer primaries. Second Prebasic Molt of inner primaries occasionally commences before Preformative Molt of outer primaries completed, resulting in 3-4 generations of feathers among primaries. Juvenile rectrices are often entirely replaced but, when retained, these are contrastingly narrow, bleached, and abraded.

First Alternate Plumage

Present primarily Mar–Sep. Most one-year-old knots replace few feathers or show dull or Basic-like Alternate feathers; appear similar to Formative Plumage during the first boreal spring and summer (Belton 1984, Blanco et al. 1992), as is found in many shorebirds (Chandler and Marchant 2001). Individuals that molt more extensively show variable amounts of pale rufous feathering below but are usually intermediate in appearance between Definitive Basic and Definitive Alternate plumages (Cramp and Simmons 1983). Individuals over-summering on non-breeding grounds average less reddish than those that migrate to northbound stopover locations or breeding grounds (Pyle 2008). Ageing criteria described under Formative Plumage (above) are useful to distinguish First Alternate Plumage as well. Molt contrasts often become more pronounced due to the increased degradation rate of retained Juvenile feathers compared with replaced Formative feathers, especially very worn retained outer Juvenile upperwing greater coverts, rectrices, and outer primaries or the block of Juvenile inner primaries contrasting with fresher outer primaries (Pyle 2008).

Definitive Basic Plumage

Present primarily Oct–Mar, largely on winter grounds. Upperparts largely plain ash gray, the feather shafts dark, and scapulars and median wing coverts with thin pale fringes when fresh; rump and lower back lighter gray; rectrices gray with narrow white fringes, outer rectrices often with dark subterminal band. Upperwing greater coverts and inner primary coverts with white tips; along with paler inner webs to all primaries and light borders on outer webs of proximal primaries, gives appearance of a white line running the length of the wing (as is true for virtually all Calidris) when in flight. Outer portions of primaries, distal primary coverts and alula dark brown to blackish. Secondaries, tertials, and remaining upperwing greater and lesser coverts ash gray, broadly tipped with white. Supercilium, chin, throat, and sides of neck light gray. Upper breast dirty white, with fine, brown wavy bars that may extend laterally to flanks; lower underparts white; axillars light gray, some with dark, subterminal, irregularly shaped chevrons; underwing coverts duller than in other Calidris, with smudges on gray axillaries and coverts (Cramp and Simmons 1983).

Definitive Basic Plumage separated from Formative Plumage by having upperpart, wing, and tail feathers more uniform in quality and freshness: primaries and secondaries often molted by Oct (or by Feb in Southern Hemisphere) showing only one generation following replacement; basic outer primaries and rectrices broader, more truncate, relatively fresher (Pyle 2008).

Definitive Alternate Plumage

Present primarily Mar–Aug, partially or completely on winter grounds and northbound stopover locations, completely or near-completely by time breeding grounds reached. Description here focuses on Alaskan and central Canadian breeding populations (BAH). Sexes show average differences in plumage (Baker et al. 1999b, Pyle 2008).

Male. Crown and nape streaked with black and gray and/or salmon; prominent superciliary stripe brick red or salmon red; auricular region and lores as crown but with finer streaks; back feathers and scapulars with dark brown-black centers, edged with faded salmon; replaced alternate scapulars, tertials, and upperwing coverts uneven in color, with broad, dark, irregular-shaped centers and widely edged in notched patterns to variable degrees, some with faded salmon and others with bright salmon-red coloration; lower back and uppertail coverts barred black and white with scattered rufous markings. Primaries, secondaries (except tertials), most or all outer rectrices, and about half of upperwing coverts retained from Definitive Basic Plumage (see above), but more worn. Chin, throat, breast, flanks, and belly brick red or salmon red, sometimes mottled with a few scattered light feathers; undertail coverts white, often including scattered brick-red or salmon-red feathers, marked with dark terminal chevrons laterally. Underwing as in Definitive Basic Plumage. Breeding populations show average differences by sex and age; breeding males of Alaskan and central-north Canadian populations average paler chestnut to alternate underpart feathers and with more extensive white on the rear belly (Roselaar 1983, Hayman et al 1986). Males breeding in Greenland and Northeastern Canada can have mantle with many yellowish fringes and medium-chestnut underparts (Hayman et al 1986). Individuals appearing more like those of other populations can occur; differences may be based on variable wintering latitudes and effects of this on molt patterns and food resources (Pyle 2008).

Female. Similar to male, but salmon colors to upperparts typically less intense, tending toward buff or light gray dorsally; superciliary stripe less pronounced than in most males, buff rather than cinnamon, sometimes indistinct from crown and eye-line area to hind neck; alternate feathers of underparts usually duller or paler salmon than in male and mixed with whitish feathers. Scattered breast and/or flank feathers with wavy dark marks at tips in a barred pattern present in all females but absent 73.3% of North American knots (Baker et al. 1999b). Alaskan breeding Alternate-plumaged females often show more worn retained wing coverts (Tomkovich 1992) and have a deeper salmon coloration and than n.-central Canadian-breeding females; likely based on average differences in molt schedules between these populations as correlated with different wintering latitudes (Pyle 2008).

Molts

General

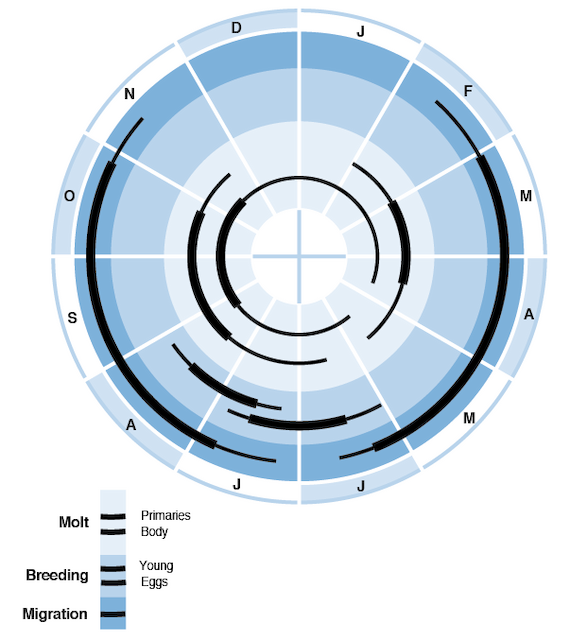

Molt and plumage terminology follows Humphrey and Parkes (1959) as modified by Howell et al. (2003, 2004). Red Knot exhibits a Complex Alternate Strategy (cf. Howell et al. 2003, Howell 2010), including complete prebasic molts, a partial to incomplete preformative molt, and limited-to-incomplete prealternate molts in both first and definitive cycles (Dement'ev and Gladkov 1951, Palmer 1967a, Oberholser 1974, Prater et al. 1977, Cramp and Simmons 1983, Barter et al. 1988, Barter 1992, Piersma and Davidson 1992, Baker et al. 1996, Higgins and Davies 1996, Harrington et al. 2007, Pyle 2008, Summers et al. 2010; Fig. 5). A Definitive Presupplemental Molt may possibly also occur in Apr–Jun on northbound stopover sites; see Definitive Prealternate Molt.

Molts can follow either a Northern or Southern Hemisphere Strategy as defined by Pyle (2008), depending on latitude of non-breeding grounds. Northern Hemisphere Strategies generally include accelerated and partial preformative molts and accelerated prebasic molts (to complete before onset of winter on Northern Hemisphere winter grounds) whereas Southern Hemisphere Strategies generally includes protracted and incomplete preformative molts and protracted prebasic molts (due to lack of temporal constraints and greater food resources on Southern Hemisphere winter grounds).

Prejuvenile (First Prebasic) Molt

Complete, Jun–Jul, on or near natal territory. No information on timing or sequence of pennaceous feather irruption and development. Presumably completed or near-completed by fledging from natal territory around day 18.

Preformative Molt

"First Prebasic" or "Prebasic I" Molt of Humphrey and Parkes (1959) and some later authors; see revision by Howell et al. (2003). Partial to incomplete, Sep-May, occurring primarily or entirely on non-breeding grounds. Variable in extent: includes most to all body feathers (lower back feathers and uppertail coverts can be retained), a few to some upperwing secondary coverts, 1-4 tertials, and variably no to most primaries and primary coverts, some to most secondaries, and two to all rectrices. Replacement of body feathers, tertials and some to most secondary coverts and central rectrices occurs primarily in Oct–Dec, at which time molt often arrests in birds wintering in Northern Hemisphere. For individuals wintering in Southern Hemisphere many individuals continue molt in Jan-Apr, replacing 1–7 medial or outer primaries (and corresponding primary coverts), 1–4 medial secondaries (distal to tertials), and additional rectrices. In these individuals "eccentric" remigial molt sequence (Pyle 2008) results in consecutive block of juvenile inner primaries (among p1–p9) and distal secondaries (among s1–s9) retained; e.g., a typical pattern may involve s1–s6 and p1–p5 retained until fall of second calendar year. A small percentage of birds may arrest primary molt such that, e.g., p5-p8 are replaced and p9-p10 retained.

Eccentric molt sequence occurs more frequently in migratory bird species exposed to greater amounts of solar radiation and includes more-exposed feathers of the wing (Pyle 2008). Sequence of outer primary molt distal as in Definitive Prebasic Molt, and sequences among secondaries and rectrices could parallel those of Definitive Molt as well; confirmation needed.

Completion of Preformative Molt as defined above, in particular replacement of outer primaries, can overlap some or all of First Prealternate Molt and occasionally commencement of Second Prebasic Molt (inner primary replacement), especially for individuals remaining to over-summer on winter grounds. Replacement of flight feathers during Jan-Apr could perhaps be considered part of First Prealternate Molt rather than Preformative Molt, if Definitive Prealternate Molt also includes outer primaries (see below); but it appears homologous with the Preformative Molt in other shorebirds and birds that lack Prealternate Molts.

First Prealternate Molt

Limited to partial (sometimes absent?), primarily Mar–May, commencing on non-breeding grounds and often completing at stopover locations or breeding grounds in individuals that migrate north in spring. Variable in extent: includes a few to most body feathers, no to a few scattered upperwing coverts, and sometimes 1-2 tertials and/or central rectrices. In w. Europe replacement can include feathers of throat, upper breast, side of breast, and scattered head, upper back, some scapulars, occasionally uppertail coverts, much of belly, and many median upperwing coverts (Cramp and Simmons 1983); individuals such as these that migrate north during first summer may average more feathers replaced than those over-summering on winter grounds. Flight-feather replacement described above under Preformative Molt (see above) can overlap First Prealternate Molt in timing.

Second And Definitive Prebasic Molts

Complete, primarily Jun–Oct but extending to Jan–Feb in individuals wintering in Southern Hemisphere (Fig. 5); occurs primarily on southbound stopover locations or on winter grounds but body-feather molt can commence on breeding grounds before migration. Second Prebasic Molt can commence as early as late May for individuals over-summering on winter grounds, occasionally overlapping outer primary replacement of Preformative Molt and Second Prebasic Molt often completes earlier than in older birds due to lack of breeding constraints. Second Prebasic Molt of birds (at age 1 yr) may follow more closely the timing of older birds. Primaries replaced distally (p1 to p10), secondaries probably replaced proximally from s1 and s5 and distally from the tertials, and rectrices generally replaced distally (r1 to r6) on each side of tail, with some variation possible, e.g., r6 replaced before r5.

Timing of Definitive Prebasic Molt can vary geographically among breeding populations, as reflected primarily by latitude of winter location (Pyle 2008, Summers et al. 2010). In Europe can begin with scattered feathers on chin and body, but most molt occurs after southward migration begins, earlier in transients of breeding populations in Greenland and northeastern Canada (late Jul–late Aug) than in those that breed in the northern Palearctic (mid-Aug–mid-Sep, or not until Oct–Nov) and/or winter in Europe (Cramp and Simmons 1983). In both of these groups body molt becomes heavy with loss of p1, and all body feathers, secondaries, and rectrices are replaced when p10 is fully grown, averaging about 2.5 mo after loss of p1. Second Prebasic Molt of non-breeding birds can begin in w. Europe in late May–mid-Jul with loss of p1, completing with p10 from late Jul or (in South Africa) from Jul to Dec (Cramp and Simmons 1983, Summers et al. 2010). Individuals wintering in Australia show similar timing to molt as those that winter in South Africa (Barter et al. 1988, Barter 1992).

Southward-migrating individuals in the Mingan Archipelago in Quebec, James Bay in Ontario and Massachusetts during Jul and early Aug (mostly bound for South America) show molt of ventral and dorsal body feathers, but rarely show any flight-feather molt (Taylor 1981). Body-feather molt can be arrested before departure (PMG; Harrington et al. 2007, Hope and Shortt 1944). Adults captured later than Aug in New England and many caught in southeastern states show advanced Prebasic Molt of ventral and dorsal body feathers, and sometime show active molt of primaries, secondaries, and rectrices. This flight-feather molt appears to be virtually completed before these knots move to se. USA winter locations during Oct and Nov (Harrington et al. 2007, 2010b).

Little is known about the flight-feather molt of individuals wintering in n. Brazil; available evidence shows that they may molt in their non-breeding areas and/or at southbound stopover locations. An adult photographed in flight in Ceara on 24 Aug 2009 showed wings with four inner primaries starting to grow (Redies 2011). In contrast, a knot fitted with a geolocator on Monomoy I., se. Massachusetts, when it was in active primary molt, migrated to Venezuela where it remained during the northern winter of 2009/10 (Burger et al 2012). Evidence from isotope signatures of 15N and 13C in wing feathers show some overlap between non-breeding populations in the se. USA and n. Brazil (Atkinson et al 2007), suggesting they may share molting locations during southbound migration. Of 5 individuals caught in Ceara Brazil on 20 Dec 2010, two had completed wing molt and the other three had only to molt p10 (PMG and AJB unpubl. data). Knots wintering in Tierra del Fuego resume body molt and start flight feather molt after arrival in their non-breeding areas at end Oct-early Nov (Baker et al. 2005a), when se. USA knots have already completed Prebasic Molt (Harrington et al 2010b). By December nearly all have completed basic body plumage (PMG and AJB) while they all are in active flight feather molt. By 20 Feb 1995 85.5% of 464 adults caught at Río Grande had completed molt of flight feathers (Baker et al 1996).

Definitive Prealternate Molt

Partial to incomplete, Feb–May (Fig. 5), commencing on non-breeding grounds and often completing at northbound stopover locations or on breeding grounds. Includes some to most body feathers, a few to most (up to 50%) upperwing coverts, 1-4 tertials, and/or 1-4 central rectrices. Males reported to replaced more feathers than females but confirmation of this needed in light of variable sex-specific appearance to alternate feathers. Molt begins on breast and underparts and includes head, neck, back, scapulars (scattered Basic scapulars sometimes retained), sometimes part of back and rump, usually some or all uppertail coverts, usually 2–3 inner or longer tertials and some or all tertial coverts, and no to about half of median and greater upperwing coverts (occasionally some lesser coverts). In Argentina body molt begins in Tierra del Fuego early Feb–mid-Mar, with heavy molt during Mar ending mid-Apr as far north as Lagoa do Peixe. In n. Brazil body molt appears to commence at a similar time; of a catch of 35 adults in Campecha, Maranhão on 15 Feb 2005, 32 were in active body molt, with 11 showing traces to 25% breeding plumage. Most migrating birds in Delaware Bay in Apr-May are not in active body molt (Baker et al. 1996, 1999a, Antas and Nascimento 1996, AJB, PMG).

Battley et al. (2005) report a possible Definitive Presupplemental Molt in Great Knot (C. tenuirostris), an extra replacement of some alternate body feathers in Apr–Jun on northbound stopover sites, which could also take place in Red Knot. Alternatively, this replacement could pertain to protracted and suspended prealternate molt in some individuals, interacting with great variation in appearance of alternate feathers of these species; study needed. In addition, some Definitive Plumage shorebirds with eccentric Preformative Molt and extensive Prealternate Molts can apparently replace outer primaries for a second time on non-breeding grounds (e.g., Peason 1984, Balachandran and Hussain 1998); this could also occur in Red Knots. Also documented in Indigo Bunting (Passerina cyanea); it is possible that this replacement is part of the Definitive Prealternate Molt (Wolfe and Pyle 2011), which may have implications on molt terminology during first-cycle molts of Red Knot (see Preformative Molt).

Bare Parts

Bill

Horn-colored in newly hatched chicks; black year-round in juveniles and adults (BAH).

Iris

Dark brown at all ages.

Legs

In newly hatched chicks legs and feet grayish yellow, with some dusky spots. In juveniles, yellow to greenish gray. In adults, dark gray-black, sometimes dark olive-gray in putative subadult knots (BAH) and adults (PMG). Some knots with diverse degree of leucism have bright yellow legs and light greyish bill (Given et al. 2011, González 2012).

Measurements

Linear Measurements

On the basis of museum measurements of adults collected Apr–Jun, females are slightly (but not significantly) longer-winged than males; females have significantly longer bills than males (Table 1 and Tomkovich 1992b). When locality is taken into account, adult female knots in the western U.S. areas (roselaari) have significantly longer bills and wings than males (Tomkovich 1992b), but there were no significant differences between the sexes among specimens from ne. U.S. (rufa).

Comparisons of wing and bill lengths within sex and age categories from ne. and w. U.S. locations, summarized in Table 1, show that Atlantic specimens tend to be shorter-billed and shorter-winged than western specimens.

Live-trapped samples of Atlantic birds in different parts of the hemispheric flyway all show significant sexual dimorphism with females averaging larger than males, except in the small sample from Maranhão in N. Brazil (Table 3). Nevertheless, there is extensive overlap in size between the sexes, and thus assignment of gender cannot be made accurately with biometrics (Baker et al. 1999b). Females are also significantly heavier than males just before departure on the southern migration from the stopover site in Mingan Archipelago, Quebec (Table 3).

Mass

Varies seasonally, with lowest mean mass during early winter (125 g) and highest mean values during spring (205 g) and fall (172 g) migration (see Table 2; see also Migration, above, and Food habits: nutrition and energetics, above).

Subspecies C. c. roselaari breeds in Alaska and winters along the Pacific Coast. It is the largest and longest billed of the six forms. ; photographer Gerrit Vyn

Subspecies C. c. rufa breeds in the Canadian Arctic and migrates and winters across the Atlantic Coast. It averages slightly paler than the Alaskan subspecies below. The following is a link to this photographer's website: http://www.flickr.com/photos/oceanites/.

Subspecies C. c. rufa breeds in the lower latitude Canadian tundra and winters along the Atlantic Coast. The subspecies are best told apart in alternate (breeding) plumage.; photographer Gerrit Vyn

During spring migration, there is great variation in the extent of breeding plumage shown by adults. Note that the bird in the foreground is largely rufous below, whereas the bird in the background is still mainly in basic plumage. The following is a link to this photographer's website: http://www.flickr.com/photos/oceanites/.

Note plump body and thick-necked build typical of this species, along with the medium-length thick black bill and dingy yellow legs. Aged as a juvenile by uniformly crisp plumage with black subterminal markings on the upperparts. The following is a link to this photographer's website: http://www.flickr.com/photos/matt_bango/.

Aged as a juvenile based on the fresh scaly upperparts with dark subterminal bars. The following is a link to this photographer's website: http://www.flickr.com/photos/oceanites/.

In worn juvenile plumage, the scaly upperparts and black subterminal bars become less obvious, but are still more striking than an adult in basic plumage. The following is a link to this photographer's website: http://www.flickr.com/photos/oceanites/.

Annual cycle of breeding, molt, and migration of Red Knots wintering in Argentina (C. c. rufa). Thick lines show peak activity; thin lines, off-peak.